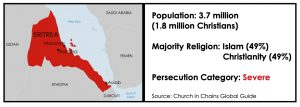

Eritrea is one of the world’s most repressive and closed countries, often referred to as the “North Korea” of Africa because of its isolation from the outside world and the authoritarian rule of President Isaias Afewerki. Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993 after a thirty-year war and the two countries fought a border war between 1998 and 2000, following which the Eritrean government became increasingly repressive.

President Afewerki, who led the fight for independence, has governed since 1993, taking complete power in 2001 after overseeing a crackdown on political opposition and anyone perceived to be a threat to the government, including Christians. In September 2001 the government closed all independent media outlets and President Afewerki ordered the detention of 28 politicians and journalists who had criticised him and had called for democracy – they have not been seen since. Most foreign aid workers were forced to leave in 2002.

Since independence there has never been an election and the constitution has not been implemented. There is no independent judicial process or independent media and unions and political parties cannot be formed. The ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice controls nearly every aspect of society and thousands of prisoners of conscience, including hundreds of Christians, have been imprisoned indefinitely without trial or sentence.

Eritreans must complete their secondary education with a year at Sawa Defence Training Centre followed by military service, supposedly for 18 months, but the government’s fear of Ethiopia means that military service (mandatory for all men and unmarried women between 18 and about 50) can last indefinitely. Conscripts receive little or no pay and female recruits report frequent sexual abuse by military commanders.

A Commission of Inquiry mandated by the UN Human Rights Council in 2016 accused the Eritrean government of carrying out crimes against humanity in a “widespread and systematic manner”.

Thousands of Eritreans flee the country every year to escape poverty, repression, persecution and indefinite military service. Leaving national service or the country without permission is considered treason and refugees are sometimes pursued for recapture by the Eritrean authorities, who may also target family members remaining behind. It is estimated that 800,000 Eritreans fled the country by 2023, the majority citing indefinite national service as the principal reason they fled.

Hopes of change rose with the signing of a peace agreement with Ethiopia in July 2018 but no reforms followed and by April 2019 President Afewerki had closed all the border crossings into Ethiopia that had been opened in September 2018.

Christians in Eritrea

In May 2002, the Eritrean government banned all religious groups except the Eritrean Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches and Sunni Islam. The crackdown on Christians followed a Pentecostal revival among young Eritreans doing military service – President Afewerki seemed concerned that soldiers who had become Christians would refuse to obey orders.

In May 2002, the Eritrean government banned all religious groups except the Eritrean Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches and Sunni Islam. The crackdown on Christians followed a Pentecostal revival among young Eritreans doing military service – President Afewerki seemed concerned that soldiers who had become Christians would refuse to obey orders.

Christians from banned denominations began to be arrested and incarcerated in appalling conditions in shipping containers, open air facilities in military camps and police stations, without charge or trial. Prisoners are denied visits from lawyers and family members and Christian prisoners may not pray aloud, sing or read the Bible. Prisoners crowded into metal shipping containers face extreme heat during the day, freezing temperatures at night and a lack of oxygen and sanitation. Beatings, torture, hard labour, filthy conditions and extreme deprivation (starvation and denial of medical care, even after bones are broken in beatings) leave many prisoners disabled and some dead.

The number of imprisoned Christians fluctuates, with prisoners often released to free space for those more recently arrested, and others kept under house arrest. Many come under severe pressure to sign documents renouncing their faith. If they refuse they are brutally punished and threatened that their families will be arrested.

Several prominent evangelical church leaders have been held incommunicado in high-security prisons since 2004. In November 2019, Dr Berhane Asmelash of Release Eritrea said, “More than one hundred have been locked up for at least seven or eight years. Of these, about forty have been imprisoned for 14 years or more.”

The majority of Eritrean Christians are Eritrean Orthodox (85%), with 7% Roman Catholic, 3% Lutheran and an unknown but growing number of evangelicals (the number is impossible to estimate as evangelicals meet in secret) and even the permitted churches face persecution.

In January 2006, the government deposed the patriarch of the Eritrean Orthodox Church Abune Antonios because he resisted government interference, refused to excommunicate members involved in a renewal movement and asked for the release of imprisoned priests who led the movement. The deposed patriarch was placed under house arrest until his death in February 2022 at the age of 94 and priests and monks seen as sympathising with him were detained, harassed and conscripted; the three priests who led the renewal movement have remained in prison since 2004.

War in Tigray

In November 2020 Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed ordered the Ethiopian Army to move into the Northern Tigray Regional State, which borders Eritrea and where many Eritrean refugees were living. Heavy fighting with the rebel Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front ensued, resulting in over 250,000 deaths from conflict, starvation and lack of medicine and the displacement of over three million people.

Eritrea sent troops to support the Ethiopian army in fighting against the Tigray regional government. Eritrean troops have been accused of committing massacres of civilians in Tigray and reportedly forced many Eritrean refugees to march to the border where they were put into trucks and driven back into Eritrea. A ceasefire agreement was reached between the Ethiopian government and Tigrayan forces in November 2022.

Helen Berhane

Helen Berhane is a Christian singer and preacher who was arrested in Asmara in 2004 after an album of her gospel music was released. She was put in prison, where she spent most of her time in a crowded metal shipping container. In October 2006 Helen was brought to hospital after a very bad beating by a prison guard. She escaped from Eritrea and eventually went to live in Denmark with her daughter, Eva, where her health gradually improved. In 2009, Church in Chains brought Helen to Ireland to speak and sing at the Annual Conference in Athlone. In 2010, Helen married fellow Eritrean Tesfaldet Meharenna in Copenhagen.

Helen Berhane is a Christian singer and preacher who was arrested in Asmara in 2004 after an album of her gospel music was released. She was put in prison, where she spent most of her time in a crowded metal shipping container. In October 2006 Helen was brought to hospital after a very bad beating by a prison guard. She escaped from Eritrea and eventually went to live in Denmark with her daughter, Eva, where her health gradually improved. In 2009, Church in Chains brought Helen to Ireland to speak and sing at the Annual Conference in Athlone. In 2010, Helen married fellow Eritrean Tesfaldet Meharenna in Copenhagen.

(Christian Solidarity Worldwide, Human Rights Concern Eritrea, Human Rights Watch, International Christian Concern, Open Doors, Operation World, Release Eritrea, Release International, Reporters Without Borders, UNHCR, World Watch Monitor)

Church in Chains in Action

Church in Chains has campaigned with several other organisations for many years to raise awareness of the persecuted church in Eritrea. Each year, Church in Chains participates in an annual protest vigil at the Eritrean Embassy in London, which is also accredited to Ireland.

Church in Chains has campaigned with several other organisations for many years to raise awareness of the persecuted church in Eritrea. Each year, Church in Chains participates in an annual protest vigil at the Eritrean Embassy in London, which is also accredited to Ireland.

In summer 2017, Church in Chains launched a postcard campaign encouraging supporters to send postcards to President Afewerki and Estifanos Habtemariam Ghebreyesus (the Eritrean Ambassador to the UK and Ireland, based in London) appealing for the release of Christian prisoners.

ERITREA: 27 Christian teenagers imprisoned following raid on house

They were arrested while gathered together for praise and worship

ERITREA: Protest vigil marks twenty years of imprisonment

Four organisations call for release of prisoners

ERITREA: TWO DECADES IS TOO LONG!

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the imprisonment without charge of six Eritrean pastors.

ERITREA: Rev Ghirmay Araya dies in prison

Rev Ghirmay Araya has died after almost three years in a maximum-security prison

ERITREA: More Christians arrested

Many Christians were forcibly removed from their homes in three Eritrean towns on 24 April