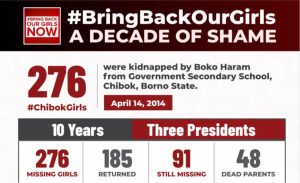

Sunday 14 April 2024 marked the tenth anniversary of the abduction of 276 schoolgirls by Islamist extremist organisation Boko Haram from their school in the village of Chibok in northeast Nigeria’s Borno state. Mostly Christians, they were students at Government Girls Secondary School where, on 14 April 2014, they were packed into trucks and taken away to Boko Haram’s hideout in the vast Sambisa Forest.

Sunday 14 April 2024 marked the tenth anniversary of the abduction of 276 schoolgirls by Islamist extremist organisation Boko Haram from their school in the village of Chibok in northeast Nigeria’s Borno state. Mostly Christians, they were students at Government Girls Secondary School where, on 14 April 2014, they were packed into trucks and taken away to Boko Haram’s hideout in the vast Sambisa Forest.

During the ensuing years many of the “Chibok schoolgirls”, now young women, were rescued, freed in exchange for Boko Haram prisoners or escaped, but around 91 remain missing. Many of the girls were forced to marry their abductors and it is believed that most of those still missing are living with their husbands and children in Boko Haram camps in the Sambisa Forest.

Some of the women who escaped have rejoined their families, but those who return with children fathered by Boko Haram militants are often seen as Boko Haram collaborators and face stigmatisation in their communities, rather than welcome and support.

Others live with their captors in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, in housing provided by the state governor. These women have chosen to remain with their husbands, who have handed themselves in to the authorities and have undergone a deradicalisation programme, and they have chosen to remain in the Muslim faith to which they were converted. This situation causes great pain to the women’s families.

Borno’s Governor Zulum told the BBC, “My only interest is that we don’t want these girls to go back to the bush again. Even before they came out [of the Sambisa Forest], some of them gave us conditions – that they will not come without their husbands.”

An escapee named Aisha Graema, who has one child, told the BBC that she would not have left the forest if she could not be with the militant she married two years after being abducted. She explained: “We have been married for eight years. I first came out of the forest and then he followed me. There in the bush, we had no relative, no brother, no sister, that is why we decided to come out. He finished deradicalisation before we were allowed to stay together. The government welcomed us well, gave us food, shelter, everything.”

Another escapee, Mary Dauda, said that she would not have been able to escape from the militants’ hideout in the forest without her husband’s help. “We had agreed that he would join me afterwards and present himself to the governor for rehabilitation,” she said.

The BBC reports that further education has proven to be a source of frustration and disappointment for those who have escaped or been released. The government pays for those who wish to resume studying to attend the elite American University of Nigeria (AUN), with no other option available. Many of them have struggled to keep up, however, and some have dropped out. They say they would have liked a choice.

The first girl to escape from the kidnappers, Amina Ali, now lives in poor circumstances with her daughter in Yola, five hours from Chibok by road, farming to pay for her daughter’s education while studying herself at AUN. “We didn’t choose AUN because we know the school standards are difficult for us, we girls come from poor backgrounds,” she said. “The former minister forced us to come to this school.“

Amina has attended AUN since 2017 but reportedly is not close to graduating. Only one of the former captives has graduated.

Disappointment at government failure

Negotiations led to the release of around one hundred girls in 2016 and 2017, but after that the government eased off its rescue attempts and rebuffed international offers of help.

Swiss negotiation Pascal Holliger told the Guardian, “We knew too that dozens and dozens had converted and had been married off, and therefore, they were kind of irrecuperable. Our understanding was that after they were married off, they left and went wherever their ‘husband’ went – so they were no longer part of the Chibok group per se. It was never very clear exactly how many were then remaining after that 103 had been freed.”

Negotiators who spoke to the Guardian said other concerns also shaped decisions on the viability of any military raid, including fears that the girls might be killed in the crossfire or that there might be suicide bombers.

Families say they have been told negotiations for the release of the remaining girls are still going on, but negotiators say talks have ended.

The Chibok kidnappings gained huge media coverage through the global #BringBackOurGirls campaign, supported by former US First Lady Michelle Obama.

The Chibok kidnappings gained huge media coverage through the global #BringBackOurGirls campaign, supported by former US First Lady Michelle Obama.

Its co-founder Aisha Yesufu is critical of efforts to rescue the remaining women, saying: “It has taken this long because they are the children of the poor, and, if you are poor in Nigeria, you are faceless, nameless and voiceless.”

The publicity surrounding the Chibok kidnappings led to resentment in parts of the northeast, where it was felt that the Chibok girls were being favoured over other groups abducted by Islamist militants.

Mass kidnappings now common

In the decade since the Chibok kidnappings, mass abductions have become so common that they are much less widely reported. Last month alone, Boko Haram gunmen kidnapped four hundred people from Internally Displaced Persons camps in Borno state and armed herders kidnapped at least 287 students and teachers from a school in Kuriga, Kaduna state; at least 130 have been rescued. More than 1,500 schoolchildren have been abducted since 2014.

While some kidnappings have been carried out to destabilise Christian communities or for ideological reasons such as Islamist opposition to education for girls, many are now carried out for ransom to fund militant groups.

Amina’s story

Amina Ali, the first of the Chibok girls to escape, was found at the edge of the Sambisa Forest by a civilian force after escaping from the militants’ camp in 2016. She had married Mohammed Hayyatu, who claimed he was forced to join Boko Haram months before the Chibok abductions, and they had a child.

The Guardian reported that Amina did not want to get married but chose marriage over being a sex slave. She explained, “The picture I got was that I would be used by a man old enough to be my father, and that when he gets tired of me, he’d hand me over to someone else again. That’s how my life would continue and I would give birth to many children that I’d need to leave with different people, so I just chose to get married to one man.”

Amina planned to escape but reportedly postponed her attempt when Boko Haram threatened to cut the hands off two girls who had tried to run away. Her husband eventually helped her escape. She is no longer with him and says her family has embraced her and her eight-year-old daughter Safiya, but adds that her daughter is often bullied for being a “Boko Haram child”.

Amina’s best friend is still in captivity. “I think about her every day,” she says. “We want our sisters back.”

(BBC, Guardian, International Christian Concern, Open Doors)

Map: Church in Chains

Poster: Bring Back Our Girls